Sunday, January 31, 2010

Day 189/365 That'll Be the Day

Thanks to YouTube, now we can hear Buddy's voice for ourselves, self-recorded for his own purposes.

The background: In 1956, Buddy Holly recorded several songs in Nashville , working with producer Owen Bradley. Bradley would later become famous producing Patsy Cline, Brenda Lee, Loretta Lynn, Conway Twitty and others. One of the songs Buddy recorded was "That'll Be The Day". Unfortunately, Owen Bradley hated rock n' roll, and the production was horrible. The songs were left "in the can". As a result of Decca's seeming lack of interest, Buddy ended up in New Mexico, recording That'll Be The Day with his own arrangement. This would become the famous version, the monster hit of rock n roll.

The problem was his contract with Decca. Decca owned all rights to the songs Buddy recorded. According to his contract, he couldn't release any version of them. He decided to call Decca and try to get a release from them. For some reason, he secretly taped the conversation.

Decca refused to give him the rights to his own song, but fortunately for the world, Buddy eventually violated his contract by releasing his version of That'll Be the Day.

Here's Buddy Holly, in his own words, fifty-three years ago:

Buddy Holly, R.I.P. February 3, 1959

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

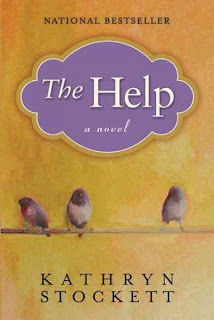

Day 188/365 Remembering The Help

I've just finished one of those books - those rare ones that are so amazing I dread turning the last page. The ones that make me (a speed reader) slow down and savor the way the author uses words as if they were tiny paint brushes meant to create a landscape in the readers mind.

I've just finished one of those books - those rare ones that are so amazing I dread turning the last page. The ones that make me (a speed reader) slow down and savor the way the author uses words as if they were tiny paint brushes meant to create a landscape in the readers mind.

Last time it was Thirteenth Tale, this time it's The Help, by Kathryn Stockett (a southerner herself born in Jackson, Mississippi and raised by a black domestic in the 1960s).

The basic premise tells the story of several women in the south, including Skeeter Phelan, just graduated from college in the early 1960s, moved back home to Jackson, no engagement ring on her finger, and no prospects. The other women include her circle of semi-friends, mostly married. That circle grows to include the black women who work for those friends when Skeeter gets an idea to collect the stories of black maids: what it's really like to work for a white woman, how bad and,in some cases, how good it is.

I'd just like to say I didn't notice the dialect one way or the other. So I'm thinking that means it rang true. I found the most direct hit by this author- the most accurate observation - was the sense of questioning and confusion between black and white women. It was (to para-quote Dickens) "the best of times, the worst of times." Times in the early 1960s were changing at a dizzying speed, age-old customs were falling by the wayside faster than they could be acknowledged, and whatever was understood to be true in the evening would be turned upside down by morning, no matter who was involved.

And as a thank you to Ms. Stockett for this book, I'll tell you my own story. My father and his four brothers were raised by a woman named Kathleen. His mother, and her family for as far as she could remember, were all raised by black women. My father was born in 1929, and until 1980, Kathleen continued to work for my grandmother. As a child, when my family visited, from the moment we walked in the door, I answered to Kathleen. She ran the household, the meals, and the children with an iron hand.

When my grandmother passed away, Kathleen retired. My grandmother left her $5000 and her personal set of Samsonite luggage. I have no idea of Kathleen's last name. I never met her husband, or her children. I have a vague memory of my dad driving my grandmother to Kathleen's home with food when her husband passed away. We have never seen her since my grandmother's funeral. Yet, she was an integral part of the household for at least 55 years.

My dad's family was fairly well-off. My mother's family was not, being instead poor rural Virginia farmers who were very accustomed to doing for themselves. When we lived in Louisiana, we were the only family on our street that did not have "help". My mother simply couldn't see the need for it, coming from her farm background. All of my friend's families had maids. It was literally a way of life - having someone else to come in daily to clean your home, run your errands and raise your children.

To this day, I have no memory of any of my friend's parents, but I remember every maid' s face and name. My best friend next door, for all intents and purposes, rarely saw her own mother. All questions and requests for playtime were referred to the maid.

The closest we ever came to having a domestic was at nursery school at church. This was the very youngest of the Sunday School groups, and the black woman that ran it was named Doretha. I remember sitting on her lap, having gotten in trouble for something.

There were thousands upon thousands of black women working as domestics in the 1960's south. I have no doubt there are still a few in some forgotten corner of Mississippi or Lousiana. Now almost every trace of them has disappeared, except in the memories of those white children they raised, and in the memories of their own children.

Ms. Stockett's book brought all those memories back. It is an intricately crafted book for those trying to sort out how they feel about things they may have forgotten.

I've included some excerpts over at While Reading To The Dog. Nothing like the whole book though -it's one to savor. You can find a copy at Amazon -there's a link on my bookshelf.

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

Day 186/365 School Days

Now I have a child in her second semester of college and for some reason neither of us can remember, it seemed like a smart idea to sign her up for math class at 9:30 am. What we did not take into account was the forty minute drive to get to class and the additional hour necessary for actually getting up and dealing with dogs prior to leaving, in addition to the absence of available parking at her community college.

Community colleges, if you haven´t heard, are experiencing an explosion in popularity. Enrollment is off the charts, their classes are packed, and every classroom is scheduled back-to-back, hour to hour. And so are their parking lots. I spent Monday driving our car around, while my daughter attended her math class, while approximately 100 of her fellow students circled alongside me. It is a daily "Christmas-Eve-at-the-mall" parking jam.

Initially, I was drafted to drive down with her simply because of the mountain roads and the major variables in weather we have here, plus she´s not particularly into driving one way or the other. Now I find my primary function is to babysit the car, until there´s available parking. After finding the parking spot, my reward is an uninterrupted hour or so of free time to spend reading, writing my blog, or catching up on sleep. I never get uninterrupted time at home, so this is a huge perk.

I also get to see what sort of people are jamming these parking lots. I remember my college days and it occurs to me how easy it is to go off to college anywhere when you are 18. There´s that uncertainty of youth, new experiences, all that. And money of course is always a stress, as well as maintaining grades to keep what financial aid is received. But most 18 year old students are single, without children, and if they're at a four year college, chances are the stress of money is falling for the most part on their parents.

During this morning’s free time, I spent 20 minutes helping the student parked next to me rock her car back and forth, trying to get the transmission to catch, so she could go pick up her sick kid, drop her off at her mom´s, while making it back in time for her noon class. She still has a paper due for last semester that she hasn´t quite finished, which means she might not qualify to stay on financial aid. After class today, she has to go to work, and sometime this evening will be able to pick up the kid, fix dinner at home, study at some point, and tomorrow morning do it all again. There is no money for replacing transmissions, and no idea how she will get to school for classes without a car, much less get to work.

This parking lot is full of these students- people who are not 18, do not have parents to help with the bills, have children of their own to take care of, barely-running cars, mortgages and rent to pay, food to put on the table, and if they are lucky, sometimes a part-time job paying not much more than minimum wage. Many of the students had real, life-sustaining employment a couple years ago. Now they are re-inventing themselves, literally in the moment.

They are not at school for beer parties, joining sororities, or extracurricular activities. They expect the teacher to be prepared and make it worth their time and money. These are some serious students.

Our main reason for having our daughter start community college was financial. We do not want her to incur a large debt for an education that may or may not lead to employment. While I’m a product of a four year liberal arts education and I believe in the value of that experience, I don´t think it is an essential experience for this generation.

What I´m discovering is that the biggest advantage to the community college experience is not the financial savings, but the exposure to the wide variety of students.

Students that take their education seriously, and fight on a multitude of fronts to get to class everyday.

Monday, January 11, 2010

Day 185/365 Stable Art

For the last three weeks and probably the next three weeks, my livingroom and office are torn apart for a frenzy of bookcase installing, painting, and purging of ten years worth of homeschool materials. Moving anything at our house demands an understanding of the domino effect, meaning five things have to be moved before I can move the thing I actually wanted to move in the first place.

So far my office is half-way disassembled with the re-painting almost finished, and the bookcases are assembled and in place in the livingroom. After the bookcases went in, the pictures were hung, mostly to get them up out the reach of curious cats and rambunctious dogs.

Over the bookcases in the corner, I've hung an unusual pen-and-ink drawing. It's been stashed away behind an armchair, waiting patiently, pretty much the same way it spent approximately 80 years of its life.

Over the bookcases in the corner, I've hung an unusual pen-and-ink drawing. It's been stashed away behind an armchair, waiting patiently, pretty much the same way it spent approximately 80 years of its life.

Our previous house was built in 1900, complete with a stable in the backyard. The stable had four stalls, and an overhead hay loft, with big swinging doors. By the time we purchased the house in 1992, the stable had long since been reincarnated as a garage. When we crawled up into the hay loft, we found various pieces of trim and lumber, and assorted "stuff" from the original owners.

We also found this placed carefully next to a thick joist, face-up against the roof:

An unframed meticulously detailed sketch of a country lane, rural farmhouse to the right with a stone wall, towering trees to the left, and in the background, barely visible, a village, complete with church steeple.

An unframed meticulously detailed sketch of a country lane, rural farmhouse to the right with a stone wall, towering trees to the left, and in the background, barely visible, a village, complete with church steeple.

This original has the pencil signature of E.C. Rost, 1890. E.C. Rost was an amazingly prolific engraver back in the late 1800's up until 1904. He was the son of a well-known engraver but actually started his own career as an oil painter, with landscapes exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York. By 1887, this versatile artist had moved into engraving (the Library of Congress owns 63 etchings by Rost), spending the next nine years furiously producing contemporary scenes of American life (rural farmhouses, canals, and villages).

E.C. Rost was an amazingly prolific engraver back in the late 1800's up until 1904. He was the son of a well-known engraver but actually started his own career as an oil painter, with landscapes exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York. By 1887, this versatile artist had moved into engraving (the Library of Congress owns 63 etchings by Rost), spending the next nine years furiously producing contemporary scenes of American life (rural farmhouses, canals, and villages).

Then one day in 1894, as he wandered among the street stalls in New York, he found two of his engravings offered for the cut rate price of $2 each. This enraged him, resulting in a lawsuit against his agents (Fishel, Adler and Schwartz Co.), not only because they had forged his signatures to the artists proofs, but mostly because (as he testified in court) the prints were worth $5 each. He was so angered by this legal confrontation that he never produced another etching, moving entirely into the new field of photography.

Today, the National Archives holds 21 of Rost's photographs, and the Library of Congress maintains another 26, all of early 1900s Cuba.

Researching our engraving on the net, an unusual number of people seem to have found them in the same sort of odd places we did: stuck behind walls, tucked into attic joists, stashed facing backwards in old pie safes.

Many are unsigned, more than a few are signed in ink, with the copyright of Fishel, Adel and Schwartz Co, and a very few are signed in pencil, like ours. I have no idea what this means in terms of whether it's an original original, or just an original copy. But it's an actual pen-and-ink, with a pencil signature.

Meanwhile the gilt frame was from another estate sale, same time period, and just begging to be paired with E.C. Rost - it's a marriage made in heaven. And a engraving with a history.