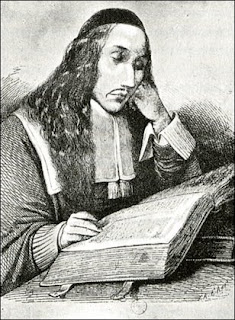

Spinoza's Selections, Edited by John Wild -1930 Red Cloth Edition~Rounding to the top and base of spine from shelving~Previous Owners Name Inscribed on First Loose Endpaper~*1* word written neatly in margin on page 286, as well as *3* vertical lines at various points in the introduction.

Usually people fall into one of two categories: those who mark in books and those who don't.

Those who don't are sometimes obsessive. Not only do they not mark in books, but they do not dog ear pages to mark their place, nor do they scrawl their names across the inside front cover, much less pencil their initials on the forepages. God forbid they should grace the book with their own personal illustrations or provide running commentary in the margins.

And then there are those who DO mark in books. In them, outside of them, on the spine, on the foredges, on the endpapers, on the title page (HAPPY BIRTHDAY FROM GRANDMA!), sometimes on the table-of-contents (stars besides which chapters are important), underlining, circling, highlighting, sometimes making notations in the margins that show orgasmic agreement with the author (YES!!!YES!!!YES!!!) or equally disdainful contempt (i.e. the short but expressive WTH?), and of course, let's not forget the artists among us, gracing endpapers with everything from stick figures to a detailed pencil illustration of the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine.

As a book re-seller, I adore the first group - the non-markers. Nothing like finding a pristine 1880's edition that looks as if it had never been opened, much less marked in.

(On the other hand, was that owner so shallow that he simply bought books that looked good on the shelf? Did he spend his lifetime surrounded by a beautiful library, just to impress his visitors, but never cracking open a single volume? Poor sad man- now he has my pity.)

As a reader I think I prefer those that simply must make their mark upon the printed book, if for no other reason than I know they actually opened it, and read a bit (and sometimes enough to provoke a strong reaction).

The marks themselves tell a great deal about the one who made them: engineering books tend to have solid, ruler-straight, red-pencil underlining, with to-the-point notations (always in very

careful lettering). I always wonder if engineers have a specific class for this -instructing them how to comment in their textbooks?

My favorite was the U.S.S. Maine illustration. It was drawn in great detail on the inside of a army textbook with the date February 15, 1898, and was almost as detailed as this painting from Uncle Sam's Navy, courtesy of the U.S. Naval Historical Center.

The young man who drew it would have been immediately caught up in the Spanish-American War that shortly followed, and his illustration (and the one above) were that generation's equivalent to our memories of planes flying into towers. No wonder he (or his family) kept that textbook for so many years.

The young man who drew it would have been immediately caught up in the Spanish-American War that shortly followed, and his illustration (and the one above) were that generation's equivalent to our memories of planes flying into towers. No wonder he (or his family) kept that textbook for so many years.

Religious books are the least likely to be marked in (or opened for that matter, even the vintage ones appear to be unread). Apparently the buyers have the same premise I have concerning gym memberships: if I paid for it, it is, by default, beneficial to me.

As for Spinoza and his selections - the owner has used a fountain pen to inscribe his name on the first loose endpaper (Eugene J. Welds). What points in the introduction were worthy of a vertical line notation? Just this: Reason will lay down moral principles in calm moments, applying them to imaginary situations, thus steeling the will against catastrophe.

What one word was chosen to write in the margin? Utilitarianism, printed right besides the definition: By good, I understand that which we certainly know is useful to us. By evil, I understand that which we certainly know hinders us from possessing anything that is good.

And what of that second vertical line notation in the introduction? Our conduct transcends all rigid principles and we play on life as a great musician plays on his instrument...we have become one with God, thus we are capable of neither jealousy nor envy...God loves no one and hates no one, and yet God loves, for love is an aspect of thinking, and therefore really the essence of God.

There you have it, the secret to life, wrapped up in 17th-century rationalist philosophy.

There you have it, the secret to life, wrapped up in 17th-century rationalist philosophy.

I wonder what notes Spinoza made in the books he read. Somehow I can't picture "Happy Birthday, Love Spinoza". Much easier to visualize "WTH???" in the margins, and possibly a little 1600's stick figure drawn on the endpapers. I'm betting he was a marker.

No comments:

Post a Comment